This weekend at Dance Place, Dance Metro DC presents the works of two up-and-coming local choreographers, Chandini Darby and Kyoko Ruch.

Both artists hail from the DC metropolitan region and have settled in DC for the time being to pursue careers as professional dancers and choreographers.

The artists were commissioned by Dance Metro DC to create original dances for the presentation this weekend, which takes place Saturday, March 18 at 8pm and Sunday, March 19 at 7pm. Their works explore themes at the intersection of personal history and our socio-political milieu.

Chandini Darby is a Washington, DC native. She is the 2015 recipient of The Kennedy Center’s Local Dance Commissioning Project. Professional credits include: Deeply Rooted Dance Theater (Chicago, IL), Washington Reflections Dance Company, Lula Washington Dance Theatre (Los Angeles, CA) and DC Contemporary Dance Theatre. Mrs. Darby is the Founder and Artistic Director of The Beauty For Ashes Project, Inc. and is currently working with CityDance DREAM as the Associate Director of Student Development. She is the proud wife of Kenny and mother to Josiah and Jazz. Her “Stances and Stanzas: a warrior’s poem” honors black poets past and present while giving a call to action for all people to use their voice to speak up and speak out. Through this visual and poetic journey the power of the poet’s voice as an integral strand of our cultural and historic DNA.

Kyoko Ruch has danced professionally with the VonHoward Project, Helen Simoneau Danse, Gin Dance Company and Company Danzante. She has performed at national dance festivals and showcases performing in her own choreography and works of her mentors and colleagues. In addition to her career in performance and choreography, Kyoko also teaches dance in the DC Metro area and has danced as a member of Company E. Her work, “Girl on Girl” demonstrates the unnecessary obstacles that women face from birth by being placed into a patriarchal society. Objectification and role-performing become the expectation. In consequence, to maintain significance and identity, women claim authority by minimizing other women.

I had the opportunity to speak with the artists this week to find out more about their evolution as dancers. In our conversation, we delved into what inspires each choreographer to make work, and they revealed sneak peek details about their performances this weekend.

How did you start dancing?

Chandini: Oh man, I started dancing young. My mom put me in dance class when I was five or six. I liked it, but I was kind of a tomboy at that time and I didn’t like ballet. I tried acting and had an agent, then I tried sports like basketball and track. I was doing recreational dance in school and a couple parents approached my mom when I was thirteen and said, “you know, she has a real talent for dance,” and so my mom put me in dance classes and after that I had a re-love, a re-birth. I was like, “Oh my god, I’m meant to dance!”

Kyoko: My older sister started taking dance classes with her friend and I wanted to follow her so I started taking ballet when I was six years old. I kept doing ballet throughout high school and it was my goal to be a professional ballerina. I was always put in the sugarplum fairy kind of roles so I had the urge to explore other things but I wasn’t too conscious of it at the time.

What genre of dance did you train in?

Chandini: I started taking ballet classes in high school; that was what I was drawn to at that time, go figure. I loved ballet, I loved modern and I was taking African, Jazz and Tap but I was always drawn more to the contemporary form. That’s what I chose to study when I went to college.

Kyoko: I did two years at Richmond Ballet as a trainee while I was at Virginia Commonwealth University. I really decided to pursue modern dance after my apprenticeship with Richmond Ballet, which didn’t lead to any ballet jobs, but I think that was a blessing in disguise for me. I feel a lot more free.

When did you start making your own work?

Chandini: This is very new for me in this capacity. I’ve always choreographed before I knew what it was. When I was young, I always saw movement whenever I heard music. I used to study music videos of Janet Jackson and Destiny’s Child and try to learn the choreography and then make my own. When I got to college, my teacher pulled me aside in my composition class and said, “you have a real knack for choreography” and I realized I could potentially do this in the future. I had so many opportunities to choreograph in college for senior projects, smaller concerts, just for fun. After graduating and going on to pursue a professional career, I wanted a family and touring for thirty weeks out of the year might not be exactly what I want to do forever. I do still love performing, which is why I’m in my concert, I think there’s a place for performing for me and I can still grow in that area. I realized that I do actually enjoy choreographing and it could be a great opportunity for me to extend my career. I wanted to see how others would respond to my work, so I applied to the Kennedy Center back in 2014 and that was the first time I started a process work from beginning to end, not just a five-minute piece.

Kyoko: When I went to VCU, I think I took a different approach to ballet after I started doing modern training, because they had me thinking more conceptually and I think it helped a lot with my actual ballet. I think my approach before was to push until I got it, without really dissecting why it wasn’t working. I started making work was at VCU in composition class. I didn’t think that I wanted to do it at all, maybe because we were getting a grade, so it felt like a burden. After I graduated, I had the urge to create. I made a Trio with three local female dancers in Richmond and I think that I really liked doing that.

What is your process like as a choreographer?

Chandini: It is a collaborative process. I’m very influenced by writing and I frequently give my dancers prompts on ‘what do you think about this or how does this affect you.’ I sometimes need to hear my thoughts on paper before movement will come out. I want dancers to have a voice in what they’re doing because that’s how they can do it their best. There’s a piece in this work which is all about celebrating being a black girl and growing up Black. Memories that are prominent that were unique about your childhood and they wrote it out, and I created a poem with all their inputs. I had them freestyle to it, and through that we developed a piece.

Kyoko: I think it varies depending on the piece. Usually I’ll try to improvise movement and record myself and write down ideas that I was thinking about while I improvised. Sometimes the concepts come from that or it’s something that I feel passionately about while I’m just living that inspires me to create. I usually have an idea of what I want to do and then I’ll try it in the studio. Based on the energy of that day and how people are feeling, I roll with what I’m seeing.

How did you choose the subject matter for the Dance Metro DC commission?

Chandini: I wanted to create a work on my own for Black History Month to honor Black poets. I love poetry. I think it’s so beautiful and relevant and has been such a thruline throughout our history. When I found out about the commission, that was the only thing in my mind. It was just ironic, we had just been experiencing this uproar of social justice movements and issues with the police and during the Civil Rights Movement, poets were speaking out about what was happening. During the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes was mirroring with his words what was happening in society and it was such a great outlet to speak on issues. There was power in recognizing that they didn’t have to fight with a vengeance but they use art to express their voices. Sometimes I feel like I don’t know what I can do; people are protesting and it’s not always where I feel most motivated. So for me as an artist, a mover, a performer, a choreographer, I feel like my best efforts are better served with my art. I can create something that is a reflection of what’s happening and hopefully spark some great conversation.

Kyoko:

The piece is based on the community I had in the ballet world. A lot of competition between the women particularly was always hidden in a sly way. When I looked at it on the macro level, I realized it wasn’t just that small community. A lot of it’s informed by media and the general expectations for women in our society. In the piece, one dancer is being born into this way that we’re living as women. The environment that I wanted to create was an enclosed space with outside forces like the male gaze that are affecting us, like we’re on display in a fish tank. She gets thrown into this world, tries to resist, but doesn’t see a way not to conform. She then submits to the idea and then I have a fight scene where it all goes down and then we call come to this realization that we need to stop putting these societal pressures on ourselves, and rise up together to achieve equality.

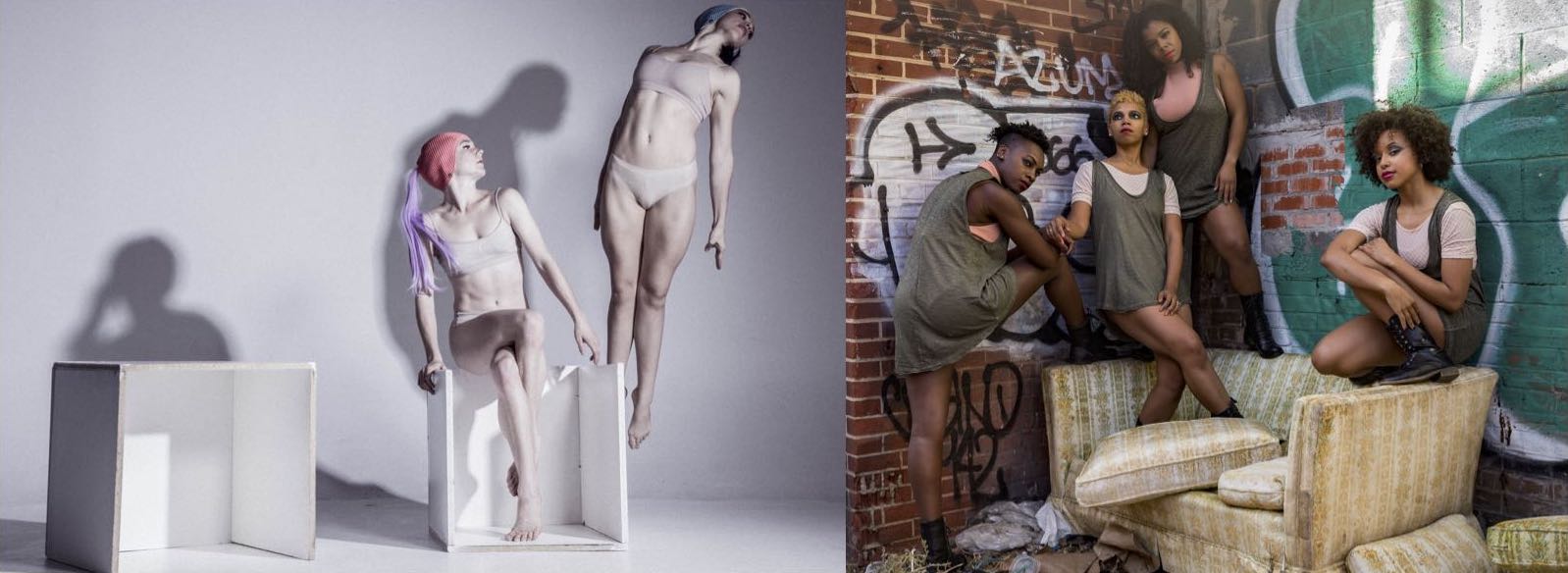

In terms of the costume design for Dance Metro DC, when I was envisioning this piece, I wanted the dancers to look like mannequins with fake hair. I had the idea of using old-fashioned swim caps in colors associated with femininity. They reminded me of Trojan helmets, which make it look like we’re going to battle with each other in the piece. It creates an aggressive look.

It’s a very scary time, but I’m hoping that what’s happening now is awakening feminism in people who didn’t know that it was important to them. I think it’s important to make work like this in times like this to counter what’s going on and bring awareness to it. We have the power so we have to insist on it.

Is the piece just dance or are there additional performance elements?

Chandini: There’s a mix. We have a poet that’s on stage speaking live with us in the opening piece. Before I commissioned her to work with us, I thought we’d do the whole thing, and then when the movement started coming out, I realized that it wouldn’t be possible because we were tired, there’s no way we could speak at this magnitude throughout the whole piece. So that’s how she came along, so she’s live in that first piece, and then there’s some recording that’s all original writing, and then I do have some original recordings of poems by Maya Angelou and Gil Scott Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” that serve as transitions.

Kyoko: The piece is contemporary dance-theater. We sing this song at the end, “Donna Donna,” that was recorded by Joan Baez and was originally a Yiddish folksong. These are why we sing it: “Calves are easily bound and slaughtered / Never knowing the reason why / But whoever treasures freedom / Like the swallow has learned to fly.” I thought that was a really important message to end it with. I had to work on making sure it ends on a hopeful note.

Does working with kids inform artistry? What have you learned from your own training that informs your teaching?

Chandini: Oh, absolutely. I think it gives me so much more information to be able to see the world through the eyes of youth, which is a very necessary perspective. The demographic that I work with mostly is inner-city, under-resourced who don’t always have a voice. Being able to see the world through their eyes is so important for me and it definitely does inspire and inform a lot of what I do. I try to be more gentle with my students. Dance can be very harsh at times, which I understand because it is an art form that deals with the aesthetics of the body. It can really break a lot of students along the way, that feeling that they are not good enough to go on and have professional careers. You want “push, push, push” to be in balance with positive reinforcement and encouragement and love. There’s a level of gentleness that is needed in the delivery and in the training process that wasn’t always there in my experience.

Kyoko:

I really like being able to share my experiences to the students, knowing how I was trained, what worked and what didn’t to guide them in the best way possible. In general, ballet training is more limiting to the creative side of the human being. I think ballet limits, because there are expectations that have to be met. It’s not as a free as modern or other types of dance. I would have had a little more nurturing of the soul.

Tickets for this weekend’s performances of Girl on Girl and Stances and Stanzas: a warrior’s poem are on sale here.

Interview conducted and edited by Rebecca Cohen

Header photos: Francisco Campos-Lopez (left), Robert Shanklin (right)